3. Think of Virtues as Social Technologies

Tippett extols virtues as tools for the art of living. This is an evolution from her childhood concept of “virtue,” when, steeped in the language of her Baptist upbringing in small-town Oklahoma, she saw it as a sort of “moral insurance policy.”

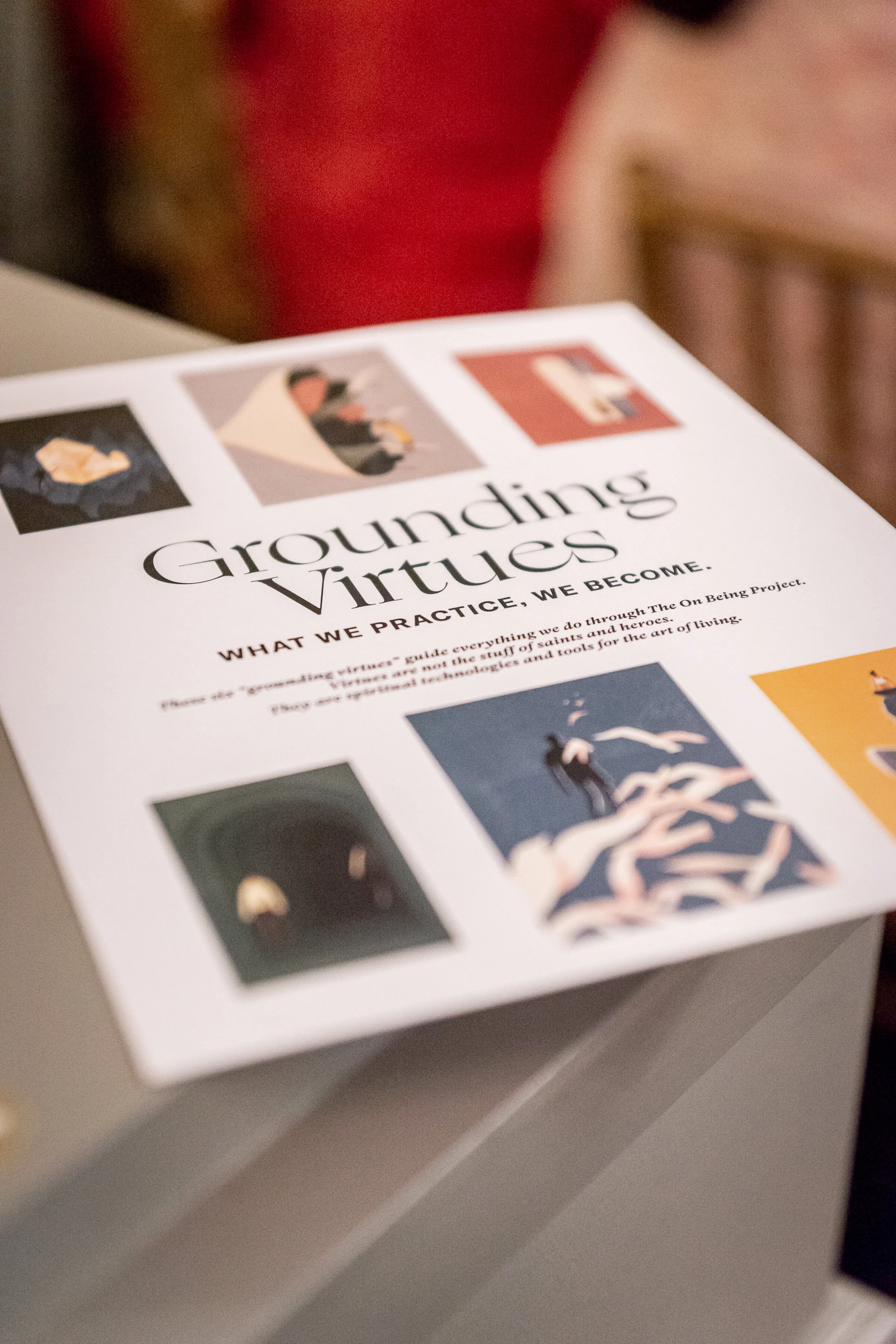

Now, she says virtues are “spiritual and social technologies… a way to attend to conduct as much as to content.”

Tippett’s closely held virtues—humility, curiosity, hospitality and love—provide a way of grounding ourselves and, if we have not yet mastered them, of practicing what we hope to become.

She speaks of the virtue of humility as “a leavening agent.” In its simplest sense, she says, it’s not about making yourself small, but about making others big.

Humility’s companion, according to Tippett, is curiosity. Are we truly ready and willing to be surprised by the other? If not, she says, it’s best to go away and work on ourselves first.

Conversation is, at its best, an invitation of sorts. To offer that invitation sincerely is to do so with hospitality. Tippett notes that offering hospitality is not the same as celebrating what feels oppositional or uncomfortable.

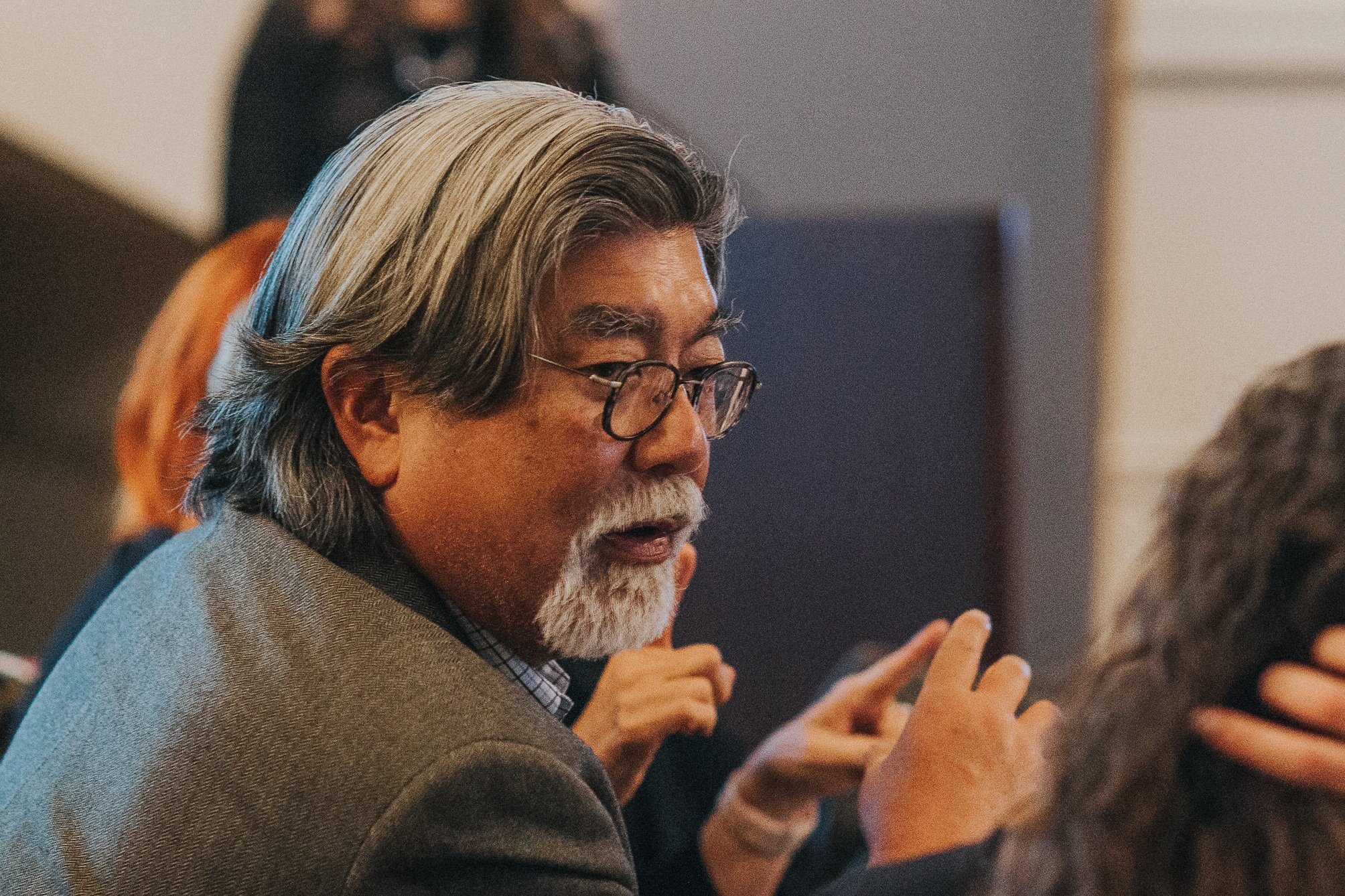

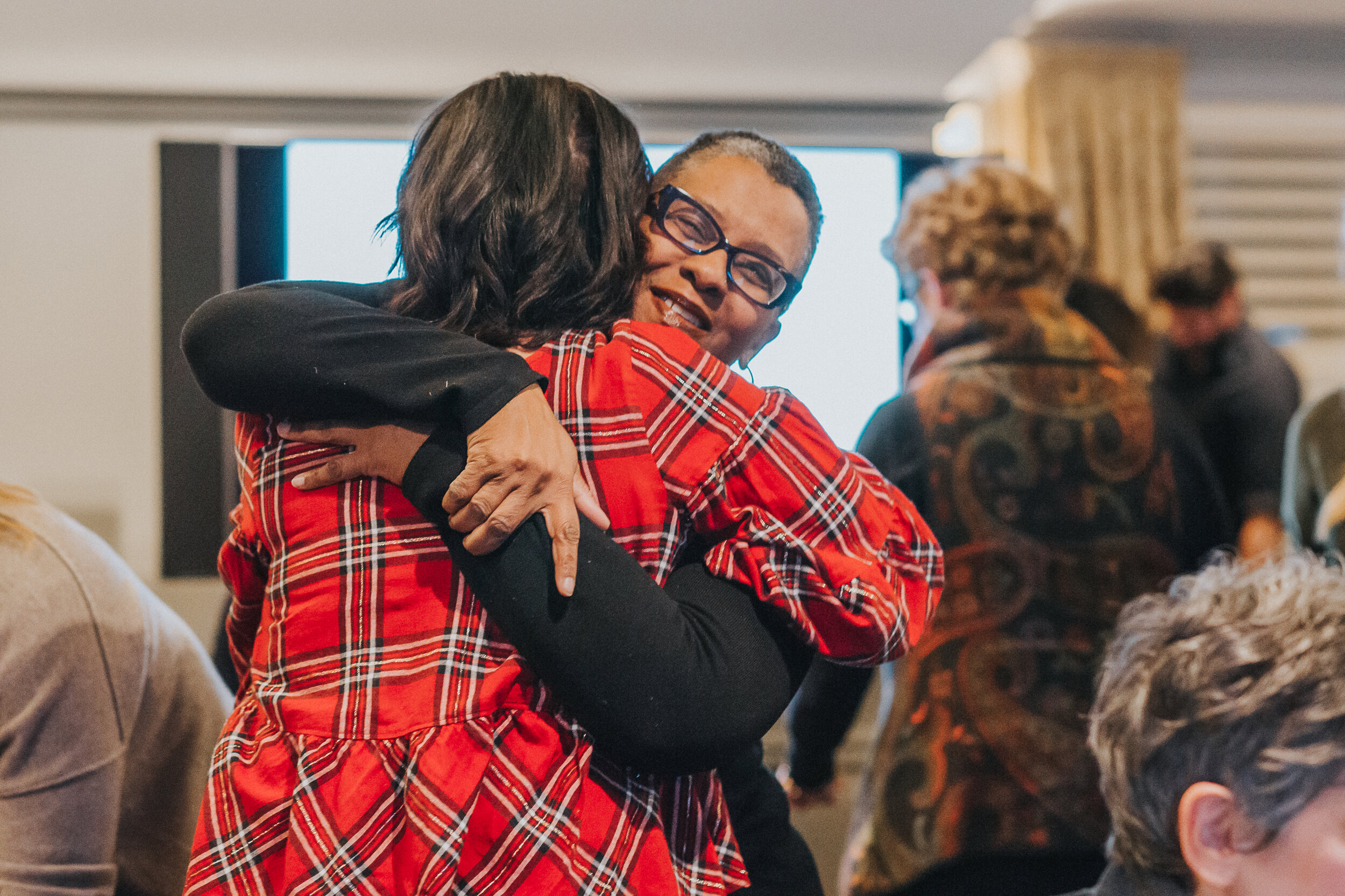

What it does do is “create a trustworthy space, in which the ground for something new can be laid.” Conversation, in and of itself, does not make the participants any more alike, but it does “fundamentally alter what is possible ahead between us.”

When we have the opportunity to converse, Tippett pleads for us to do so with the virtue most often spoken of, but so rarely practiced: love.

Love, she says, is “the only thing big enough to create the common life that our world needs and that our century demands.” Not a romantic notion of love, but the expansive love that embodies our most generous selves, and abides despite challenge or lack of reciprocation.

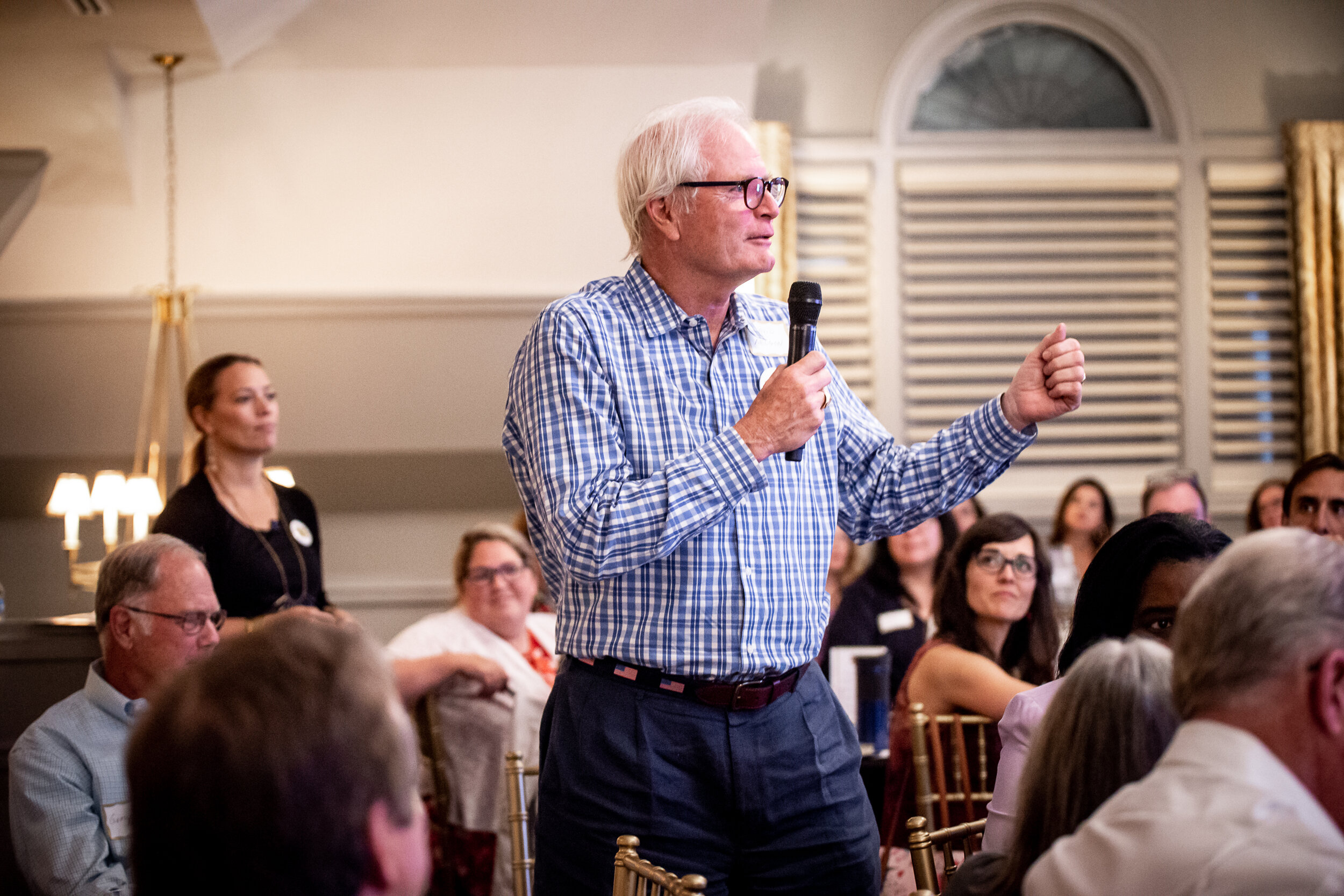

In closing, Tippett encouraged us to do our part in “making this generative story of our time.” Entering these conversations is important—maybe the most important work we can do.

“Across my life of conversation I have seen a strange, deep truth of life that wisdom emerges precisely through those moments when we have to hold seemingly opposing realities in a creative tension and interplay.” Her hope is that we will take a deep breath, open our hearts and engage.

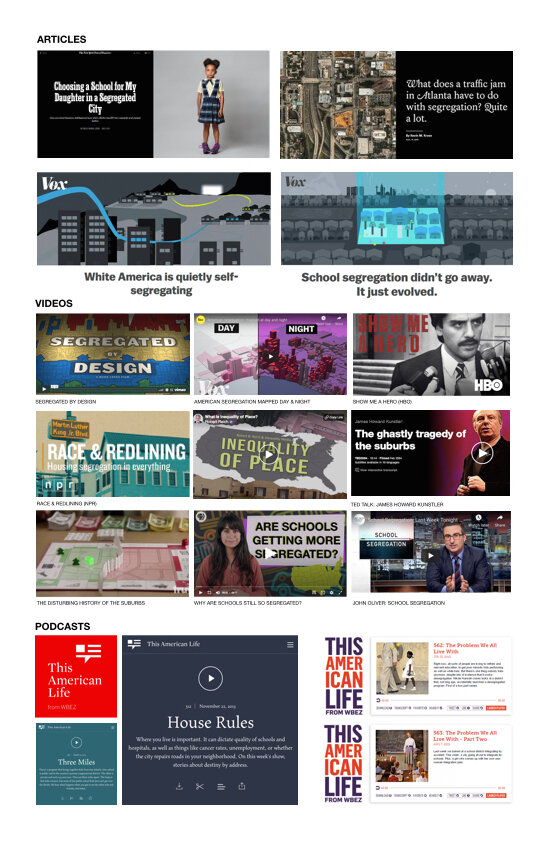

As part of The Civil Conversations Project she founded in 2011, the On Being producers created a Better Conversations Guide and outlined their Grounding Virtues. Together, they form a roadmap of sorts for locating the “crack in the middle” and forging ahead in hopes of establishing better understanding. It’s a wonderful place to begin.