(Photo: Linda M. Barrett)

BY TAMARA TABEL

The evening started with a bang — tornado warning sirens, emergency text alerts, and a brief evacuation to the basement! A memorable start for a conversation on fear & courage.

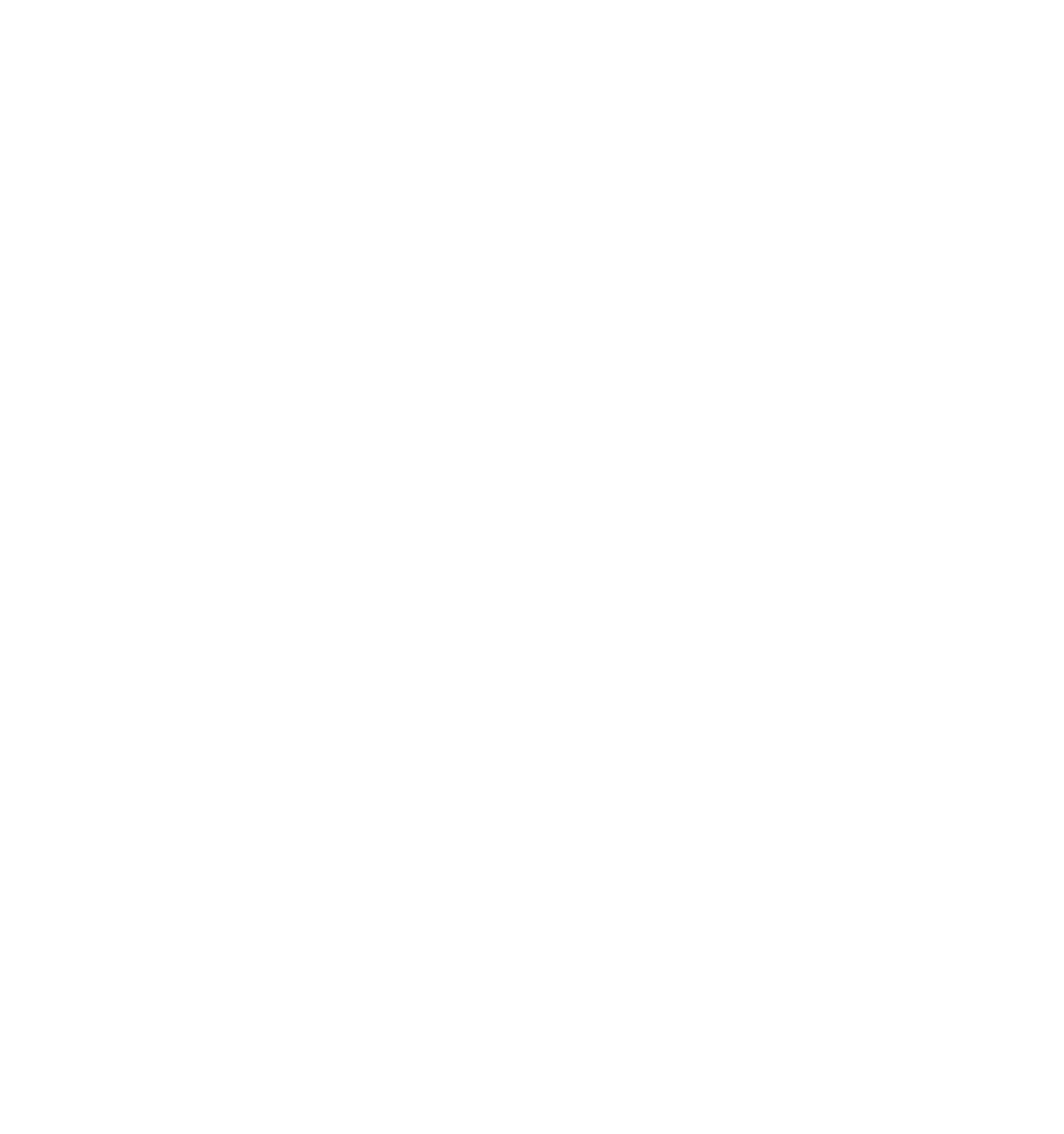

On September 11, 2019, over one hundred guests gathered at Barrington’s White House for the first of ten monthly sessions of A Year of Courageous Conversations presented by Urban Consulate to learn about the neuroscience of fear and courage, what is really going on inside our brains, and what tools and techniques we can use to respond when fear blocks our progress.

Once the storm passed, co-hosts Jessica Green and Dr. Zina Jacque welcomed guests and thanked them for their courage just to be in the room.

“I come of age in a faith that has a song,” said Jacque. “And the words are ‘Encourage my soul, and let’s journey on. The night is dark and we are far from home. But thanks be, the morning light appears. The storm is passing over.’

“The storm is passing over,” said Jacque, “when men and women stand up and are willing to be courageous—to engage with difference, to not be afraid of the grist of learning and of gathering data that is different than theirs.”

Jacque & Green welcomed guest expert Dr. Arin N. Reeves of Nextions to lead a discussion on how we already have the “courage muscle” to overcome our fears and biases.

Harnessing her background as a researcher, lawyer and academic, Reeves offers thought-provoking messages to inspire and activate change. She speaks on many forms of differences: racial, ethnic, gender, generational, religious, sexual orientations, identity and expression, physical abilities, cognitive style and cultural difference.

Reeves began by saying she is not an expert in your experience, but rather, in helping see diversity in your own thoughts.

She went on to explain the origin of fear itself.

Status Quo Bias is the Strongest

Doing things as we’ve always done them is easy and comforting. If you eat the same thing every morning, it would hit your pleasure centers to talk about that food. But if we told you we were going to take away your bran flakes and make you eat bacon every morning, a part of your brain would say, “Oh no, you’re not!”

Your brain is responding to difference. We don’t like change. But, Reeves says, “We need to dismantle these identities because it is causing us to treat people in ways we don’t intend.”

Why Do Our Good Intentions Fail?

Think how many New Year’s resolutions you’ve made—and then broken. We want to do those things, but somehow our great intentions fall away. What is stopping us?

“When our actions don’t align with our intentions,” says Reeves, “the reason is fear.”

We fear the unknown. We fear things that scare us.

The brain sees both of these as the same, as equal. So, your body reacts to a tiger the same way it reacts to your fear of public speaking or meeting a person who is different from you. Your heart races, your muscles tense, your palms sweat—sometimes just by thinking of a thing we fear.

Many of us share common fears: heights, flying, water, the dark, or fear of rejection. But Reeves cautions us to dig deeper.

“Although we have socially named these fears, it is not what we’re actually afraid of,” says Reeves. “You need to have a conversation with your brain.”

A fear of heights is actually the fear of falling. A fear of water is actually a fear of drowning. Being afraid of the dark is apprehension that we might not be able to see things that might hurt us. And fear of rejection is the fear of being unloved, of disappearing, of not mattering.

Our Fears Come From our Ancestors

“We’re descended from ‘scaredy cats,’” says Reeves.

In ancient times, a person who looked different from you likely meant you harm. Seeking similarity meant safety. If you didn’t run, you might be killed. The curious who took a closer look at that rope coiled in the grass might find out too late that the rope was really a snake.

Taking the “low road” and avoiding the different or unknown is how we’re hard-wired. “I’m not sure if that’s a rope or a snake, so I’m going to treat it like a snake and run away.”

We have the opportunity to take the “high road” and be curious. Maybe someone unfamiliar could have been the Bill Gates of a thousand years ago! But we are hard-wired to not be open.

If we see something and we’re not sure if it’s a rope or a snake, our instinct is to treat it like a snake and avoid the conversation or the experience.

Instinctive vs. Conditioned Fear

With instinctive fear, you don’t have to experience it, to be afraid of it. It’s non-conditioned—we can’t help it. We have an instinctive fear of spiders and snakes because people used to die from bites.

A conditioned fear is responsive, something we associate or attach to something else. We have a fear of rejection, so we become afraid of public speaking.

Reeves offered the example of an experiment done with Baby Albert. At nine months old, he happily played with a white mouse. Then the experimenters clanged a pan every time Albert saw the mouse. Over time, Albert was conditioned to be afraid of anything white.

However, we have repeated exposure to a false cause-and-effect. We often avoid the facts. For example, the leading fear for parents is that “Stranger Danger” will kidnap their child. But the reality is that the biggest cause of death in children under three years old is drowning in their own bathtub at home.

We feel we don’t need to know the truth. Why would we talk about what’s scaring us? It feels safer if no new information comes in. Because we’re closed to questions, we lack critical dialogue. To avoid discomfort, we avoid new experiences.

In the U.S., children have biases by the age of three—they are more positive to whiter skin and will notice if someone looks different. Upon seeing a person with a prosthetic, they might ask, “What’s wrong with you?” Children already have a sense of what “normal” is.

We turn away from what’s different. What we took in as a 2- or 3-year-olds solidified in our brain and created a circuity of “no thank you.” And if we are overwhelmed by “too much stuff” (stress, time constraints, uncertainty, fatigue) our brains default back to its circuitry.

The Power of Courage

Courage is the presence of fear, but moving forward in spite of it. Reeves says, “Being totally fearless doesn’t exist. You can’t have courage unless you have fear underneath.”

Reeves encourages us to “Think of a time when you were brave. When you felt all that stuff—a fluttering stomach, your brain saying ‘I can’t’—but you did it anyway. Whatever courage muscle you used to be brave is the same muscle that you use any time you want to be courageous. You don’t have different courage muscles—there’s just one; just one pathway in the brain. You’ve used it many times. You used it to show up today.”

She reminds us that fear is a reaction. Courage is a decision. You don’t have control over a reaction, but you always have control over a decision.

“You already know how to have courageous conversations. You just need to do it. When a person is very different from you and you don’t want to offend them, use your courage muscle.”

Courage over Comfort

“You can choose courage or you can choose comfort,” says Dr. Brené Brown, “but you cannot choose both.”

So how can we overcome that instant reaction of fear?

Reeves encourages us to hold onto our fear just a little longer. Don’t react in the moment. Give your brain muscle a chance to understand the actual fear and recognize what you attached it to. When you recognize a fear, you can calmly examine it and create an answer to address the fear. “The minute you name a fear,” said Reeves, “it has an answer.”

Dr. Reeves left the audience with a challenge:

“Talk to one person who was not here, and share with them one thing you learned tonight. You will use your courage muscle and are teaching someone else to use theirs."

“We can use our courage muscle to overcome. The more we use it, the stronger it becomes.”

Defining Courage is the first of ten monthly sessions for A Year of Courageous Conversations. Presented by Urban Consulate at Barrington’s White House in partnership with community advisors, the series is made possible thanks to support from Jessica & Dominic Green, Kim Duchossois, Sue & Rich Padula, Barrington Area Community Foundation and BMO Wealth Management. To learn more, visit CourageousConversations.us